I: PERISTALSIS

The fish that season came up rotten.

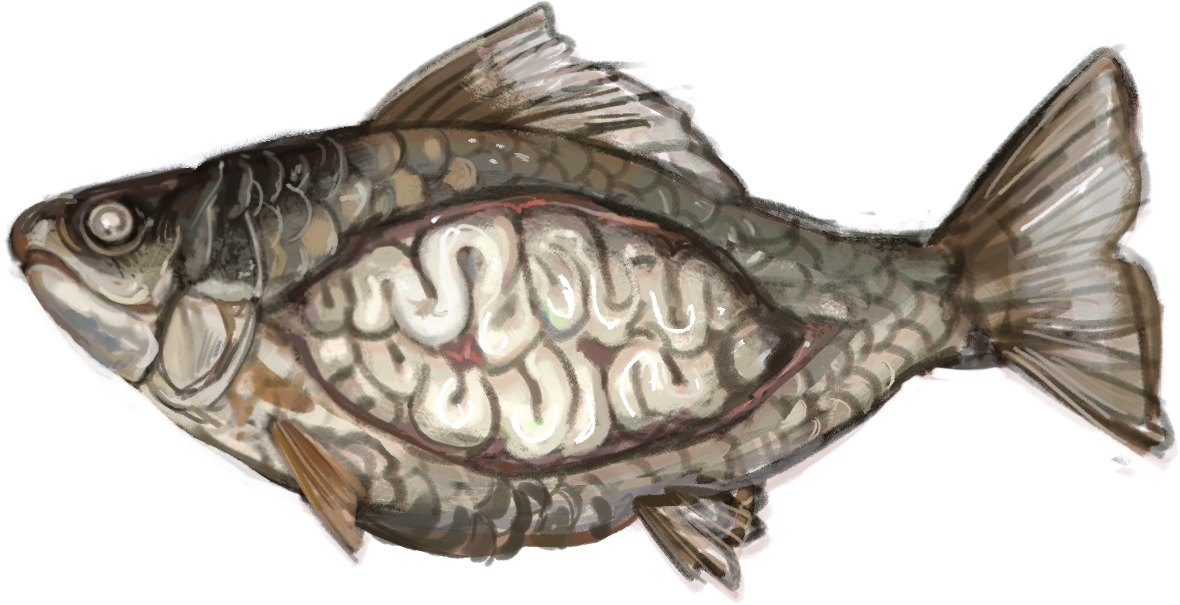

When the men cast out their nets, clumps of them breached the surface with a wretched stench. Long dead, bobbing along the waves like strange lures. They burbled up and the fishermen could do nothing but dispose of them. Not because the catch couldn’t be salvaged— the meat was pale and bloodless, untouched by decomposition— but for what the men discovered when they cut them open.

Inside their distended bellies, nestled snugly in their white intestines, the fishermen found human body parts. In one, a man discovered a fingertip severed at the knuckle. In another, a perfectly round, unbroken eyeball. A set of teeth nesting in a pair of haphazard rows. The pale, smooth curve of a disembodied ear.

Each piece was too large to have been swallowed. The corpses showed no signs of tampering, no cuts or incisions. Yet each part was perfectly intact, as though they’d formed from within like grotesque pearls.

The men of Oldegård were far from picky, but eating from this unnatural catch felt like a transgression. No good things could come from it. They couldn’t throw the corpses back to the water, so a trench was hastily dug, the fish unceremoniously buried alongside each scavenged body part. They lay in the dirt like strange, disassembled doll pieces.

There were not enough appendages to create a man wholesale, though what sort of man could be created from the disparate pieces the fishermen shuddered to think of.

The village wives, ever superstitious, whispered of the phenomenon for weeks. How the river was made to vomit as if purging itself of a great sickness. Some great force must be angered, said the frightened ones, seeking retribution. Surely something terrible was to come.

But, the wiser of them pointed out, retribution for what? The rumblings of the world were far too large to give them notice. They were but a humble fishing village— if there were tremors, it was the aftershocks of a transgression that had already come to pass.

Perhaps something terrible had already happened, they mused. Something great and terrible, deep within the earth.

Ragnvaldr’s hands were red.

His fingers were sticky with crimson, tacky, stained to the wrist. The deer lay crumpled before him, black eyes unseeing. Entrails blossomed from its stomach in thick bulging ropes.

The ribcage scraped against his teeth as he buried his face further into the gaping cavity. It wouldn’t be an obstacle. Nothing was anymore. Ragnvaldr had devoured bones, maggot-ridden flesh, sucked marrow from femurs, cracked skulls open against stone and drank the brains. Nothing in the mortal body was beyond breaking, as he had found.

Distantly, he knew the scene was abominable. He couldn’t stop. Jaw distended, muscle and sinew packed into his throat in ravenous handfuls. Constricting it all down to his gullet to meet that insatiable hunger inside him. Everything was wet. The air stank of damp fur and rust. Blood and saliva dripped down his chin into the snow.

Eventually Ragnvaldr came back to himself— the red tinge receded from his vision, the cloud of bloodlust lifting from his mind. The adrenaline left his body and left it a hundred times heavier. He sat there struggling to draw breath. His jaw ached. He closed his eyes and lifted his face to the air, feeling it sting with frigid wind.

Above him, the encompassing birch trees stretched their pale fingers to the sky. Birds sang shrill calls unseen from the canopy; the frostbitten underbrush quivered in the cold. There was no one else for miles. That would remain true if he walked many more.

Ragnvaldr looked down at what remained of the deer. It lay still. Its glossy eyes reflected a distorted ghoul of his face.

He pushed himself to his feet, the wooden prosthetic of his leg groaning under the weight.

Carefully he gathered up the slaughtered body, skinned it, and butchered the pieces until it was indistinguishable from a regular hunt. Slinging it over his shoulder, he began to trudge home through the snow.

Along the way he came across a shallow river, in which he washed his hands and face. Red coursed off him in such quantities the water stained down to the basin. It settled below the surface as a dark, shapeless cloud, swirling with crimson froth.

It was too damn bright out, Enki thought.

He was never one for outdoor life, nor nature in general. Libraries of tomes and cathedrals were his domain; he’d taken every opportunity since youth to slink further into shadow, to pore over tomes and ritual circles without having to make conversation with unimportant people. Even the dungeons with their particularly oppressive, unnatural darkness, didn’t seem so far from the cloying walls of the convent. He expected to die there, entombed in stone, without ever feeling sun on his skin again.

But Enki was here, above ground, out of those dungeons in miraculous and improbable fashion. So he would simply have to deal with sunlight spilling through the nearby window and searing his eyes, without even a curtain to block out the wretched rays.

Fortunately, it was winter, so the days were cut mercifully short. But the end of the season was fast approaching. Soon the fresh shoots would bashfully peek their stems through the hoarfrost, the snow would make way for verdant grasses, and the trees and flowers would go into full bloom. Horrendous. The thought made Enki wish to sleep for a hundred years, perhaps under a layer of dirt.

On the plus side, it would bring a fresh crop of herbs, with which Enki had many experimental mixtures to test. A benefit of living in proximity to a village was the residents’ stockpile of medicinal plants, to which they generously granted Enki access despite their awkward and uneasy interactions. (The villagers were quite unsettled by him in general; he suspected it was by the sole grace of being Ragnvaldr’s companion that he was tolerated at all.)

Herbology wasn’t particularly one of Enki’s fields of study, but Oldegårdians didn’t have much in the way of tomes. It occupied his days well enough. Identifying and sorting various flora, preparing them for vials and poultices, tying them in bundles to be dried in the sun. More difficult nowadays with just one arm, but these days he had help.

Speaking of which. He glanced next to him at the pale pair of hands clumsily attempting to tie a clump of roots together.

“Not like that.”

The girl looked up from her task, blinking at him with wide eyes. She remained silent, as always, but her expression was attentive.

“If you tie them with a knot that way, it’ll never hold. Do it like this-” He demonstrated with a clump of henbane leaves (a favorite of his for psychoactive brews). The girl watched his motions carefully.

He finished in no time at all; even with one hand, spindly fingers were good for this sort of thing. He placed the knot before the girl. “Here. Now it’ll hold strong.”

She nodded with a furrowed brow and threw herself with gusto back into tying her strings, small hands copying his movements without grace but determination. She managed to correct herself enough that the end result was functional, if not a bit lopsided.

Enki gave her work an appraising look and hummed. “Acceptable.”

The girl beamed.

Beneath the table, a large furry weight pressed on Enki’s knees, emanating an imploring whimper. Heavy paws batted at his ankles insistently.

“Absolutely not,” he snapped at the girl before she could reach down, recognizing her look of pity. “Those roots grow once a year. They won’t go to waste on a beast that doesn’t need them.”

The girl pouted, but retracted her offering. She brought her empty hand over instead to scratch between the beast’s ragged ears. Its massive head dwarfed her palm.

Moonless was twice the size she’d been in the dungeons. She only continued to put on bulk as seasons passed, helped, no doubt, by the many table scraps tossed to her by the girl and the outlander. The girl in particular seemed to have an affinity with her; despite the beast’s size and ferocity, around the girl, she was as tame as a housebound pup. They never went to the village unaccompanied— how the villagers must feel to see this scrap of a girl, parading about with a beast that could tear their limbs off at her beck and call.

The front door creaked on its hinges before it swung open with a loud creak of protest, followed by the blasting of wind. There was a series of heavy footsteps. Each off step was slightly uneven compared to the other.

Moonless shot up to greet the visitor, floorboards shaking with each step of her massive paws. Meanwhile the girl spun in her chair, startled, before a bright smile split her scarred face and she hopped to her feet. Her coordination had never excelled, she stumbled a few times; nevertheless she ran enthusiastically to greet their guest in the footsteps of the dire hound.

Enki was content to remain sunken in his chair. He was not one to expend energy and move unnecessarily. He knew who it was.

And there stood the outlander in the doorway. His mountainous outline carving a dark shape against the sky, unmoved by the frigid air and snow stinging his bare skin. There was a butchered mass on his shoulder that was at one point a carcass, which he carried like it weighed nothing. He was truly something monstrous. Enki often wondered if he was all human, or if he had been changed down in those stinking depths, as they all had.

The girl and the hound gathered around him. Moonless reared up on her hind legs and let out a cabin-rattling bark at a volume that would render a lesser man deaf. The girl excitedly took one of Ragnvaldr’s massive hands in her own and hopped in place. Her smile was bright and blinding.

Ragnvaldr paused in his movements to draw her to his side. The top of her head barely came up to his thigh. He held the girl briefly, squeezing her close, before releasing her to skip back across the room to her duties. Moonless received a heavy scratch on the head. He passed straight by Enki towards the stone-hewn kitchen, in which a cauldron was already boiling.

Enki eyed the carcass in his arms. Carved expertly, but not expertly enough to evade Enki’s attentive gaze. Uneven marks along the limbs and abdomen. Beneath a carved flap of muscle, indents in a row perfectly following the curve of incisors, canines, molars.

Ragnvaldr met him with a steady gaze. Pale eyes unblinking.

“Ragnvaldr.” Enki said calmly, plainly. “Welcome home.”

Ragnvaldr returned the gesture with a silent nod, head bowing slowly. He moved past Enki without a word and disappeared into the other room.

Enki closed his eyes, leaned back in his chair, and drew in a long breath. There was the sound of footsteps, the girl’s quiet giggles. In the other room, crackling fire and slow roasting, sizzling meat. There was water trickling outside the window, perhaps a stream, faint rainfall that would soon turn to ice in the frigid temperature.

Darkness danced behind his eyelids. Enki let the tepid sound of his heartbeat thrum in his ears and drown out all else. Everything was as it should be.

New dreams came once he left the dungeon, Ragnvaldr found. They were more vivid even than the night terrors which plagued him upon the first discovery of his village. Something about sleeping in that perverse darkness created dreams of a thick, suffocating nature, night terrors which stretched for agonizing lengths like moving through honey. The residue of them remained behind Ragnvaldr’s eyes when he woke, especially after he wished not to remember.

He sat awake after one such occasion, staring sightlessly into the room awash in midnight. The memory of the dream stayed with unfortunate clarity.

He had been wandering a maze, as he did in so many dreams now. Deep in the depths of the earth, vines crunching under his feet. He was blind, not from darkness, but from a strange obstruction in his sockets; it was solid, uneven, when he brought his fingers up to it he could not discern its nature but felt soft, velvety shapes.

He was looking for Enki, and the girl. Deep in the bowels of the labyrinth he knew he’d find them. Somewhere. He did not walk so much as sprawl on all fours, suspended forward in a fall that seemed to go on forever, yet he never hit the ground. He was floating, suspended as if underwater, dragged by an unknown current which staggered his leaden feet forward.

Distorted, chiming voices, which Ragnvaldr strained to hear; he could not pick out intelligible words, yet they sounded so familiar. Something about them settled in his chest like a heavy stone, a weight that remained long after he woke up.

Next to him, Enki stirred. His slight frame was curled in on itself like a gnarled branch. He naturally ran cold, and his gaunt chest showed little sign of movement; even after long seasons sleeping by his side it was easy to mistake him for a corpse.

Ragnvaldr kept silent. He did not wish to wake him. Enki raised his hand up to Ragnvaldr’s thigh anyway, because he had never let Ragnvaldr’s wishes stop him from doing what he wanted.

“What is it?” His eyes remained shut, but his voice was as sharp, as awake as ever.

Ragnvaldr contemplated his response for a few long moments. “A dream,” he eventually replied. “It was strange.”

“Mm.” The papery hand squeezed his leg, just once. “Do you require something for your mind?” His partner was no stranger to dreams or medicinal ways to repress them.

“No.” Ragnvaldr stared forward. “It is nothing worse than usual.”

There was a long, exasperated sigh. The bony fingers squeezed again before bracing against his abdomen. Enki hauled himself up with difficulty, mirroring Ragnvaldr’s sitting position.

He pressed his forehead to Ragnvaldr’s shoulder; Ragnvaldr felt the jut of his brow ridge and nose, the strawlike curtain of his hair, his hand against Ragnvaldr’s ribs. Ragnvaldr reached down to intertwine their fingers. Enki’s heartbeat was faint, insistent.

“You stubborn man,” Enki mumbled. “You’d better not be lying.”

Ragnvaldr let out a soft chuckle. “Of course not.”

“If you lost your mind I wouldn’t hesitate to put you out of your misery.”

“I know this. Good to hear.” Ragnvaldr ran his thumb over Enki’s knuckles. So fragile, many tiny scars. “Do you ever feel as if you left something behind in the dungeon? Some piece of yourself?”

“I did leave a piece of myself.” The stump pressed pointedly into Ragnvaldr’s ribs.

“You know what I mean.”

A moment of silence, the sound of Enki contemplating. “Yes. But truly it would have been foolish to expect any different.”

They sat there for a while.

“In my dreams,” Ragnvaldr said slowly, “it is like I never left the surface. Like I go deeper every time to places I’ve never been.”

Enki made a quiet noise of acknowledgement. “Do these places feel important?” Ragnvaldr let his thoughts drift to the golden city, the ghoulish shine of sun, the distorted faces of gods.

“Maybe. But they don’t feel tangible. If it means something I don’t know.”

“Well, we’re up here now. If something’s in that fetid dungeon, it’ll have to crawl all the way out of those wretched depths to catch up with us.” Enki gave a humorless snort. “And I doubt there’s anything at this point you couldn’t kill.”

Ragnvaldr smiled. “Thank you.”

“Now sleep, brute.” Enki leaned all his weight into Ragnvaldr’s side, which wasn’t much. “The girl needs you to take her to town in the morning.”

Ragnvaldr acquiesced. He lay back down onto the woven sheets, Enki curling up next to him like a housecat, and let his heavy eyes slide shut. The difference between the darkness of the room and the abstract dark behind his eyelids was nothing. He slid down, and down, and fell.

It was a long walk to the village, which no one seemed to mind. The trek drew them out the grove of trees, up a sandy slope of rocks and gravel and through grassy fields. Long pale reeds studded the ground which were good for weaving; the girl reached down to pluck them as they passed. She spent the trips tying them into practice knots, perched on Moonless’s back.

On Ragnvaldr’s shoulders hung the week’s spoils, all that would go to waste from their hunts, their food, their clothes hewn from hide; pelts dangling from a thick beam like a beast of burden’s yoke, he trudged forward with steady, patient steps.

Enki sweltered under the direct eye of the sun. He didn’t do well outdoors; he grimaced beneath his makeshift veil, stepping gingerly over tree roots and branches. Still he was kind enough to carry his own burden, an armful of tonics and potions wedged beneath his elbow for trade at the apothecary.

The walks were long and usually devoid of conversation save for occasions when Ragnvaldr, with his pinpoint sense of direction, noticed they were off track and redirected them back on course. Moonless sometimes went off trail to sniff at random patches and stare off into the woods, but she rarely strayed far.

The girl even found it in herself to fall asleep, lulled by the steady motion of Moonless’ ambling steps. She dozed, peacefully nestled in gray fur, beneath dappled shadows of tree leaves.

To find the village without previously knowing of it would be nearly impossible. Not due to particularly stealthy construction, but because it was so small and ramshackle it would be overlooked on any map. Humble buildings, slightly dented in and slanted by the wind. Old fences decorated with fishing wire. Every wall was scoured white by the sun. The air smelled of salt and fish.

There was never resistance to their arrival, but the townsfolk were always a little wary of this band of strangers. The few local children whispered and made fleeting attempts to get closer to Ragnvaldr. They pointed at Moonless with awe and fear. The village wives drew into close circles and whispered amongst themselves. The elders creaked in their rocking chairs, squinting eyes the color of clouds.

In the dim light of the apothecary, Enki exchanged hushed words with the woman at the counter. Glass clinked softly as various bottles were shuffled back and forth. Her hands wavered over Enki’s tonics, brow furrowed as he listed the ingredients and their effects. He had a good guess at what she was thinking. Where had he gotten this information, she wondered. How he’d gained knowledge of such varied medicine with such bizarre effects, for maladies and injuries far graver than the average person would ever encounter. Why he was so strangely familiar with rituals of forbidden practice.

Enki was quite beyond caring, couldn’t conjure it if he tried. The look in her eyes she shared with the rest of the townsfolk— one of curiosity, uncertainty, a tinge of fear. He offered no answers. He knew what he was. All the things wrong with him had roots in events too long ago to date and too profane to explain.

He was lucky in a sense. Since childhood he’d been unmoored from normalcy, unlike Ragnvaldr; upon entering the dungeon, there was no sense of a mundane life that had been destroyed. Yet he did feel changed, loath as he was to admit it. Changed in a deeper, more fundamental way, so much so that even he and his warped view of life had to notice. The darkness of the dungeon escaped alchemical study, escaped rational thought. It pushed him past his deepest limits, pulled the light and life from his eyes and replaced it with something else, and now settled in his bones.

Enki’s skin was human, gaunt as it was. He did not know if what lay beneath was so anymore.

He curtly thanked the woman for her time, and without another word, set out to the woods.

“There was another strange harvest,” said the village leader to Ragnvaldr, running a hand over the presented pelt to check for flaws. “Around the turn of the season.”

She was a stout, hardened woman, with a sparse shock of hair, white to the root, pulled into a tight bun. Her arms were tan and taut with muscle, decorated with nearly as many scars as Ragnvaldr’s own. She had many years on him in age, and most of the villagers really; deep lines scored her face, her protruding jaw, and carved a mask of stone. She was not beautiful yet could never be called ugly, for the least superficial beauty was that of age— not a year on this woman wasn’t brutally fought for, tactfully planned.

Ragnvaldr stayed silent, waiting for her to continue.

“We found a deer in the river and a flock of birds scattered around it.” She examined him unwaveringly as she talked. Her flinty gaze was sharp and unyielding as steel. “Every one of their heads missing.”

Across the room from them, the fire crackled.

“This is the fifth time in a short amount of months,” said the leader, her tone flat and even. “Since your arrival, it happens more and more. Do you know anything about this?”

“Of course I don’t.” Ragnvaldr’s fingers tightened around his knees.

“And your companions?”

“They know nothing. Have done nothing.” Ragnvaldr let out an unsteady breath. “We want to live our lives in peace.”

“Of course,” said the leader. “As do we.”

A tense silence settled between them.

“Do you remember the first time you showed up at our gates?” she asked. “It was evening. Terrible storm on the horizon.”

And Ragnvaldr did remember. The raindrops pelting his face and hair, the gray dark sky. Enki with wet hair plastered to his neck, barely visible against the clouds, only anchored to him by the iron grip of his hand.

“It was just you and your partner, then. You were very unexpected. They were all quite scared.”

The villagers’ eyes had shone out from the dark like animals. Frightened and unnerved, no one quite sure what to do. Then a figure rose behind them, gesturing to a quivering guard to raise the gate.

“You were spoke our tongue, so I listened to your story. Your village burned. Your hunt for vengeance, then your search for safety. That you had a young girl.

”I let you in on one condition. You remember what I told you?“

”You told me,“ Ragnvaldr replied, ”that if we brought trouble, you’d slit our throats.“

She hummed. ”Your memory is sharp.“

Ragnvaldr was silent.

”You have been a fine hunter, outlander.“ She ran her hand over the deerskin. ”And a fine collector of pelts. But I have kept an eye on you and your flock. I have reason to believe there’s more to your story than a simple tale of pillaging raiders.“

She fixed him in that unblinking stare. Her gaze was unreadable. ”I’ve given you the benefit of the doubt time and time again, for you have clearly experienced,“ she gestured to Ragnvaldr’s prosthetic, ”hardship. But we are cautious people. If your presence endangers our survival, we prioritize the latter.“

Ragnvaldr set his jaw and swallowed. ”I understand.“

She hummed in acknowledgement.

”These dark happenings. What makes you think we have anything to do with it?“

She was silent for a time before she hummed. ”I have only a hunch. I have learned to trust my hunches.“ She raised an eyebrow. ”That and your mutant hound who grows every time it visits.“

”You are the sole hunter of your group. How do you provide me with pelts in such quantity? You know of life in a village, how we hunt in bands. How much blood have you spilled with just your own hands? And your daughter who brings flames forth with her fingers.

Her gaze grew serious again. “I sense something in you, in your group. Something that should not be there. For now it lies dormant. But strange things have a way of attracting more strangeness to them. A more paranoid leader would have had you executed a long time ago.”

He took a deep breath. “Thank you. For not acting upon your instinct.”

“I haven’t acted yet,” replied the leader. “Whether or not that changes will be up to you.”

She motioned for Ragnvaldr to clear out of the room, going back to examining his pelts.

Ragnvaldr swallowed again. He pushed himself off the chair and slowly, cautiously, made his way out. The door creaked shut behind him. He did not look back.

“Show us again!” a village boy shouted. His knobby fingers peeked out atop the barrel he balanced on.

The girl nodded shyly. She felt her face heat with so many curious eyes on her. There were only a couple children in the village, but all of them were older than her by a couple years, taller, ganglier, less baby fat in their cheeks. Not so much older that witchcraft lost its spellbinding nature, of course.

She took another vial of water from the pile she’d been presented with. Set it before her on the ground, closed her eyes and took a deep breath. Her fingers stretched across the empty space and grasped a new material from there, pulling it forward. Beneath her hand, the water bloomed red.

A chorus of excited cries exploded from her rapt audience. Several of the children ran forward to examine the vial, holding it up to the sunlight, uncorking it and tasting sips to test if it really was wine (coy they were, most had already figured it wasn’t a trick after the fourth time she did it).

“What are you all doing?” a voice came from a nearby hut; a weary-looking midwife striding over. “That’s enough wine for you all. Shoo, shoo. To your chores.”

She waved away the children with a dented broom, scattering them back to their parents’ houses. The pile of transfigured wine vials went into the folds of her dress, rolling her eyes as she swept them out of reach of eager youth. She did not say anything to the girl but shot a glance at her over her shoulder. Her expression was something like curiosity, tinged with concern.

The girl waved tentatively after her, unsure of what face to make. Most of the villagers knew of her, even that she knew magic. None of them seemed to care much. She stuck so close to the adults in her party that she was rarely ever approached; when she was alone, no one really knew what to do with her.

For the most part, she was content with being by herself, playing with Moonless in the fields. The attention of the village children was new, a bit overwhelming. But she enjoyed them too.

Behind her, a soft touch settled on her shoulder. She twisted around to find Ragnvaldr, smiling not quite with his mouth but very much with his eyes. A set of traded supplies was slung over his shoulder.

“Having fun?” The girl nodded fervently, bouncing on her heels.

He nodded back, eyes sparking with warmth, before reaching into his supplies and grabbing something. He presented it before the girl in his massive palm— unfurling his fingers, the gift was revealed as an apple. Her eyes widened. She enthusiastically snatched it up and took a large bite.

She was so much less thin now than she had been in the dungeons. Since he’d found her in that cramped cage, eyes pale slits of fear cutting through the dark.

“Do you like it here?” he asked softly.

She nodded again, cheeks full.

“Have any of the villagers said anything to you? Anything bad?”

She shook her head in the negative.

He pulled her forward into a one-handed embrace, palm braced against her back as she pressed her cheek to the side of his wooden prosthetic.

Her arms, which could barely encircle his leg, squeezed him close.

The air smelled of dirt and loam. Branches curved dark and dense far above Enki’s head, blocking out all sunlight.

He had to commend the apothecary; their herb garden was more competently set up than even his old acolytes’, funneling mulch and waste to a secluded grove away from contaminating factors or wandering hands. Not to mention the relief from sunlight. He closed his eyes just to relish the feeling.

Leaves crunched under his boots as he trailed forward, following a path delineated by shrubs twisting vines. The distant call of birds echoed deep from within the hollow in chorus with insect song, the sound of rushing water.

The garden itself was sequestered away, hidden more by foliage than man-made objects. Nevertheless, Enki quickly uncovered the wooden gate latch nestled among the branches and tugged the door open.

What hit first and immediately was the wave of smells, sharp and pungent, the tang of fresh, growing leaves. An eden of herbs and exotic plants teemed with life. All at his fingertips. Enki was rarely grateful for things in life, but at the sight of the lush, verdant green, a twinge of gratitude for whatever gods were still alive stirred in his battered heart.

He took his time foraging. Indulgently examining each sprig, tossing away those that were wilted or pest-bitten. Here, he could afford to be picky, rather than scraping up any scrap he could find from the dirt to desperately rub into open wounds.

Footsteps crunched behind him, he instinctively prepared a black orb spell before finding, to his annoyance, the great lumbering hound padding after him with a wagging tail. Her tongue lolled out her mouth, leaving on the ground disgusting pools of saliva. She tilted her massive head at him with an inquisitive whimper.

“Beast.” He gave her an irritated look, but let the spell dissipate between his fingers. “You’re usually with the girl. Eager for someone else to bother?”

She trotted to his feet and pressed her wet nose curiously to his hands.

“Well, since you’re here, behave yourself,” he said to her dryly. “Don’t eat anything you’re not supposed to. And don’t piss on the herbs.”

The hound was already wandering off, distracted by some circling insect. He rolled his eyes and got back to the forage. Mainly he was looking for roots; experimenting with tinctures, he’d found that their healing properties could potentially surpass the leaves and stems in potency. Thus he was crouched up in the dirt, pale fingers raking through the loose earth.

Moonless was growling at something. She often was. The cave from which they’d found her, in which she’d presumably been born, was filled with hostile life. It was a miracle they placated her at all, the ferocity she’d greeted them with.

He paid her no mind until he realized the direction she was snarling in. Not into the woods in an abstract direction like he’d thought. Her great head was bowed towards the ground, facing something.

Now this was concerning. Enki slowly stood and walked up behind her to see the subject of her aggression. Her ears were pressed back, lips peeled back to reveal even more of her jagged teeth.

On the floor was some sort of lumpen creature. A dead one, Enki was able to identify immediately— he knew the sight and smell of rot better than anyone. It was long gone, but couldn’t have been rotting more than a couple days.

A rat, Enki realized. This thing on the ground used to be a rat.

The strange thing about it, though, more than its inexplicable presence in this otherwise walled-off area, more than its twisted body which was hairless in patches and mottled gray, was the growth sprouting from its haunches. It looked almost like a fungus. But it was not, to Enki’s eye, who had previously watched flesh decompose and blossom into a million colors and shapes. This was not decomposition like Enki had ever seen.

A flower was sprouting from its back, dark red petals, leaves delicate and quavering. It sprouted towards the dark, blooming wide despite the presence of no sunlight at all.

Enki did not approach any closer. He took five steps back, dragging Moonless with him. Raising his flesh hand, he twisted his fingers and the tiny flower burst into a controlled flame, withering to black ash alongside the rat’s cadaver.

Eventually there was nothing. For good measure, he kicked dirt over the smoking remains.

Moonless stopped growling, but she did not stop warily looking in the direction where the corpse had been. Enki did the same. She was smarter than he gave credit for, he supposed, about these unnatural sorts of things.

Enki picked up his foraged herbs, tucked them under his arm. He headed towards the garden’s exit and heard Moonless follow after.

A pounding migraine began to coalesce in his skull. He pressed his lips in a thin line. He did not feel surprise, nor fear, at this predicament. His capacity to feel those things were long weathered away, scraped away like rocks in a tide.

Still, there was a sense of something encroaching. He couldn’t deny it. What that thing was, he knew immediately and instinctively, that it was beyond his bounds of understanding. Perhaps would always remain outside of it.

How frustrating. But such was the way of things, and always had been.

Enki stepped into the sunlight and grimaced, squinting against it, but resigned himself to the discomfort, knowing what the darkness now held. Idyllic life as it was would not last. There would be no more relief in the dark, none at all.

The birds sang overhead, clear and crisp as a mountain spring.